LONDON, U.K.—Is cultural appropriation ever an accident? What about cultural appropriation of cultural appropriation? These are some of the questions brought up by British artist Anthea Hamilton’s installation The Squash, currently at Tate Britain.

The Squash involves a wandering model dressed in a variety of costumes which include squash-like headpieces. Originally, the Tate’s website stated that Hamilton was inspired by a photograph of a person dressed as a vegetable lying among vines, but she did not remember where she had seen this photograph. Hamilton told Vogue, “The starting point of the work is a found image I’ve had for many years. It shows a person dressed in a costume like a squash, pumpkin, or gourd. I no longer have the caption for it, so cannot trace it. It’s a wonderful mystery. I don’t know what the purpose of that image was, so the only way to get to know more about it was to try and make my own version of it.”

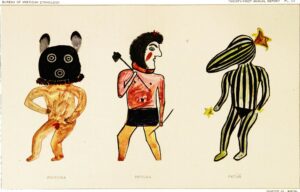

When Joanne Prince, owner of Rainmaker Gallery in Bristol, saw pictures of The Squash costumes, however, they looked awfully familiar. She posted the photograph on her Facebook page with the caption, “Looks like a Hopi melon head to me!” She wasn’t the only one who thought so. (“Melon head” is one term for squash katsina, also known as “Squash Kachina” or “Patung.”)

“I first saw the image on the front page of The Guardian newspaper and was surprised that a Hopi figure was featured so prominently on a national newspaper,” says Prince. “I read on and was dismayed that the artist was firstly not Native and secondly had replicated an image whilst completely forgetting its attribution.”

Prince tagged several Native artists in her post, including Diné-Chicana painter and muralist Nani Chacon, who called for people to write to the Tate. Prince says, “I wanted the issue to be raised directly by Native people as their concerns would have more impact.”

Chacon, along with other artists and curators, contacted the Tate, and on April 4, Prince noticed that the museum had changed the wording on its website, which now reads as follows:

Prince said the addition helps but could go further. “I am glad that some reference to origin has now been added, but I do not think that it is enough,” she says. “This high profile instance is not merely inspiration but replication.”

Hamilton has not made a statement about the change, but presumably, she now remembers where she found the image. Interestingly, it turns out that her appropriation was inspired by another artist’s casual cultural appropriation. Does that make her less guilty? In the age of Google image search, probably not. But it does highlight the ongoing challenges that occur when imagery and symbolism are taken out of context by people outside Indigenous communities.

1 Comment

I’m glad this article was written. I was so alarmed with the Squash exhibition first hit, alarmed that not many people were calling it out as an exact replica of Patung Kachina